The Maryland Archaeological Synthesis Project: One State’s Solution to Archaeology’s Crushing Gray Literature Problem

Maryland Archaeological Synthesis Project

Introduction

Since passage of the National Historic Preservation Act fifty-three years ago a growing body of valuable data has been generated by state agencies, CRM professionals, and preservation officers. Unfortunately, this data is usually trapped in an archaic paper-based format, restricted geographically to a single state archive. All too often the data is brought to light only to be “reburied” in the SHPO’s library where it may be largely inaccessible to researchers scattered throughout the country. This paper describes how the Maryland Historical Trust is addressing this problem through the establishment of a secure, online, searchable catalog of raw data and CRM reports.

Defining “Gray Literature”

Within Archaeology, a substantial body of print data exists in a form typically classified by the library science community as “fugitive” literature or more commonly by archaeologists as “gray” literature. A considerable amount of time and attention has been dedicated to defining what gray literature is, its strengths and weaknesses, and methods of providing access to it (Warnick 2001, Denda 2002, Seely 2005, Stock and Schöpfel 2003, Owen 1997, Harrison 2005, Schöpfel 2006). While the defining characteristics of gray literature and the motives for creating it are debated within the library community, the key factor that sets it apart from traditional monographs or serial publications is the mode(s) of distribution used. Alberani and De Castro (2001: 237) define gray literature as, “material that is not circulated through the usual commercial channels, not easily found, not always available, etc.”. Commercial publishers are not involved in the dissemination of gray literature. Any form of profit typically takes a back seat in the effort to distribute the material and, thus, access to such literature can be difficult or nearly impossible. At any rate, access does not come through the “normal” avenues of bookseller, journal subscription, or library.

Research librarians have pointed out that obtaining comprehensive information on specific archaeological sites is a particularly challenging issue for them, in large part because of the proliferation of gray literature within our field (Seely 2005: 2, Adelman and Markson 1987). If this is a problem for research librarians, then surely it is a problem for the community of archaeologists. Dr. Dean Snow, former President of the Society for American Archaeology lamented as recently as 2010 that despite the proliferation of a number of useful online tools providing access to archaeological data in recent years, vast troves of unpublished CRM reports remain inaccessible or very difficult to access (2010: 350).

In the United States, this state of affairs has been exacerbated by the growth in research driven by compliance with the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966 (Snow, et al. 2006, Lattanzi 1999, Childs and Corcoran 2000) and similar state laws, and now even local ordinances in some areas. Publically-funded archaeology has also produced a similar proliferation of gray literature in other parts of the world (Adelman and Markson 1987, Cohen, Murowchick and Kao 2018). Unfortunately, this data is often restricted geographically to one or a few government archives in a given state. In the United States, the State Historic Preservation Office (SHPO) that reviews CRM work usually becomes the final repository for compliance-driven archaeological reports. Any given SHPO’s library is often inaccessible to researchers scattered throughout the country, resulting in the effective “reburial” of archaeological data that has only recently come to light.

Another factor in the proliferation of gray literature is a dramatic expansion in the scope of the data that archaeologists recover. Innovation in data recovery and analysis methods have made the recovery of ethnobotanical remains, animal bone, debitage, sherdlets, and other materials a part of routine recovery, while archaeologists of an earlier era would have discarded or overlooked these materials. As a consequence, “[t]he level of documentation now demanded by our discipline impedes the function of the publication process as a tool to preserve the archaeological record” (Kansa 2005: 98). The result is that less and less data is being disseminated through traditional publication channels and more is being consigned to gray literature or is not circulated at all. This adds to the sheer volume of gray literature and with no ready method by which to cull through it in pursuit of a particular research topic, synthesis and data integration become next to impossible (Kansa 2005: 98, Snow 2010: 352).

Gray Literature and Archaeological Synthesis

The explosive growth of gray literature, particularly compliance-driven research reports, creates some serious problems for regional archaeological synthesis and study of specific research questions. Synthesis of archaeological research is built upon past experience. But what happens when a given researcher’s sphere of “past experience” is skewed towards data that has been generated through one process (i.e. academic or grant-funded research) at the expense of another (compliance driven work)? The “big picture” gets warped! The only way for archaeologists to begin drawing accurate conclusions is if data from the past is readily available from both “pure research” and “compliance” perspectives (Bradley 2006). In addition, data generated as a result of compliance-driven research is publically-funded. This data was largely collected at the public’s expense, but if it is not incorporated into syntheses of archaeological research, it remains inaccessible to the public (Snow 2010: 352, Lawrence, et al. 2014: 3).

In 1998, a survey was conducted by the Council for British Archaeology in which both archaeologists and lay readers were questioned about why archaeological project publications and archives were being under-utilized in the British Isles. The results of that survey pinpointed the boom in archaeological gray literature as one of the most pressing issues. There, as in the United States, this “boom” has been largely generated by CRM research (what is called “developer-funded” research in Britain). The survey revealed that many researchers simply did not consult such literature and, “that those others who might wish to use it are often not doing so, chiefly because of their unawareness of its existence or difficulties of access” (Jones, et al. 2001: 6.2.2). This survey was conducted during a period of explosive growth in Internet technologies and the potential that these new technologies held for solving the problem of access did not go unnoticed in Britain.

In conjunction with the survey, a consortium composed of the Council for British Archaeology, several British universities, and other agencies began working to provide online access to archaeological gray literature through the Archaeology Data Service portal (ADS 2018). This valuable resource provides free access to summary site reports that have been uploaded by participating CRM professionals, academics, and governmental agencies. In addition, data archives, scanned library resources, and even online data analysis tools are made available free to the public - all searchable via web-based applications. Millions of archaeological site and monument records from throughout the British Isles have been uploaded into the ADS databases and the service’s ADS Library includes links to nearly 300,000 bibliographic records, including scanned site reports (ADS 2018). While the Archaeology Data Service does not offer complete coverage (participation is voluntary), it is a far more comprehensive effort than has been implemented in the United States. The influential British prehistorian, Richard Bradley, criticized the apathy of many of his colleagues towards developer-funded (i.e. CRM) research, stating that any synthesis of archaeological knowledge which ignores such gray literature is bound to be erroneous (Bradley 2006). If syntheses of British archaeology can be faulted, with ready availability of CRM reports through the Archaeology Data Service, how much more questionable must synthesis research in the United States be?

To be fair, it is not as if this problem is being ignored by American archaeologists. Increasing numbers of researchers in the United States are exploring the potential of Internet technologies to provide access to archives of digital archaeological data. One can look back as early as the 1980s, when National Park Service personnel began advocating for the creation of a centralized database of bibliographic references for archaeological work throughout the country. The National Archaeological Database (NADB) was a compilation of over 350,000 bibliographic references for research reports and analyses, a majority of which could be classified as gray literature (CAST and NPS 2015).

The evolution of the Internet brought with it increasing calls for the online publication of similar bibliographic reference lists, and also the documents themselves. A growing number of publications and conference presentations have begun to focus on issues of “cyberinfrastructure” in archaeology (Kansa 2005, Snow, et al. 2006, Kintigh 2006a, Kintigh 2006b, Snow 2010, Rivers Cofield and Reeves Flores 2014, Kintigh et al. 2014). Many of these authors specifically note the inadequacy of synthesis which does not take into account “unpublished” data forms. They argue that the creation of cyberinfrastructure would simultaneously preserve data and provide wider access which would aide synthesis and lead to more accurate archaeological interpretations in general.

And American archaeologists are putting their money (or at least their creative energies) where their mouth is. The Archaeology Data Service in Britain has already been mentioned, but in the mid-2000s, the ADS began working with the Center for Advanced Spatial Technologies and a consortium of universities, not-for-profit research institutes, and CRM professionals calling itself “Digital Antiquity” (formerly Archaeoinformatics.org) to produce an international cyberinfrastructure for archaeology (Digital Antiquity 2018). This consortium has developed software prototypes and infrastructures for preserving and providing access to digital archaeological data such as text, images, GIS, research databases, and the like. The tangible outgrowth of their work has been the tDAR (the Digital Archaeological Record) database, which at last check included over 390,000 document records (Brin 2018).

A number of smaller-scale efforts are also underway, focusing on more restricted geographic areas or particular topics of interest. Boston University’s International Center for East Asian Archaeology and Cultural History, working with a broad consortium of Asian universities, research institutes, museums, and cultural heritage agencies has been building a database of bibliographic records for both published and unpublished works of archaeological interest (Cohen, Murowchick and Kao 2018). A significant proportion of the records being incorporated into the so-called “ARC/Base” database are government mandated site reports. The quantity of such reports in East Asia is expected to grow rapidly in the next few decades as new laws in China, Korea, and other Asian countries begin to drive excavation in the same way North American cultural resource management laws have driven research here (Cohen, Murowchick and Kao 2018). Another example is the Museum of Underwater Archaeology’s (MUA) Gray Literature Bibliographic Database. The MUA project includes bibliographic references for Phase I and II submerged resources reports, as well as redacted copies of the reports in some instances. This database currently includes references for 296 reports from 5 Atlantic seaboard states and a few federal agencies, but is working to incorporate data from more states (MUA 2018). There are numerous other examples scattered across the web of similar projects focusing on particular subsets of data.

In recent years, a number of State Historic Preservation Offices have taken steps to begin making state-curated archaeological data available over the internet. A recent review of SHPO websites undertaken by the author revealed that 24 states currently offer online access to some or all of their site file data. Several others report that they are currently working towards that goal. But of these 24 states, only half (AR, DE, GA, IL, LA, MD, NM, NY, OR, PA, WA, and WY) appear to offer some level of access to CRM site report data via the internet. Most of these states provide access to either 1) a subset of the gray literature reports available in the SHPO’s physical library, or 2) search functionality for scanned CRM report abstracts or summary reports. Most of the states either offer the archaeological data through a password-protected website accessible only to professional archaeologists, or through a paywall which helps to cover the costs of maintaining the data. One state, Delaware, has scanned all of the gray literature reports related to Department of Transportation projects and made them freely available to the public, but the reports have been heavily redacted to protect site location data.

Obstacles to Online Gray Literature

Before we see more widespread access to CRM gray literature data online, a number of obstacles need to be overcome. First and foremost among these is the now archaic format in which most of the gray literature data has been collected: paper-based reports. While many SHPOs now accept or even require the submission of CRM reports digitally for review and compliance purposes, every state has a significant backlog of print reports in their libraries.

In a geographically quite small state such as Maryland, the CRM backlog consisted of approximately 3,700 reports just a few years ago. This represents many hundreds of thousands of printed pages of data. With such sheer volume at the outset, it can be daunting to contemplate how to even begin addressing the problem. Though it is tempting to think that improvements in the efficiencies and costs of scanning technologies and optical character recognition software should allay concerns with volume, state budgets typically prioritize existing programs over new initiatives. On one level, it may be more practical and cost-effective to build searchable databases that cover only the incoming gray literature while ignoring the print backlog. However, it is not sufficient. In order for true archaeological synthesis to take place, databases need to be comprehensive and cover both print and digitally-submitted reports.

Another major obstacle is the SHPOs’ responsibility to protect site location data. Government employees are obligated under several pieces of federal and, in many cases, state legislation to protect site location data (Carnett 1991: 6-7). Obviously, this limits the ways in which CRM report data can be provided to the public. However, as others have noted (Snow 2010: 352), this data was collected at significant public expense and there is also an ethical obligation to make the gray literature data available to the public on at least some level. SHPOs often find themselves caught in a tug-of-war between these two disparate obligations. Again, this can lead to an unwillingness to tackle the problem, or at the very least, uncertainty about how to go about doing so.

Finally, the sheer volume of data contained in a typical CRM gray literature report can be an obstacle in and of itself. In Maryland, cultural resource management reports can routinely run upwards of 300 pages in length. Compare this to the typical gray literature report available through the British Archaeological Data Service: while reports sometimes do approach 300 pages in length, the vast majority appear to be 30 or fewer pages.

The reasons for this disparity are the subject of an entirely different paper, but the bulk of CRM reports in the US can actually be an impediment to research. Investigators tend to have a fairly narrow topic of interest in mind. Even if a given researcher is able to locate a report of potential interest, the manuscript may be so large that it is not easily digestible. Having read thousands of these reports, I suggest that perhaps brevity is not valued highly enough in American archaeology. It can be quite difficult to get a “feel” for a site when so much of the really valuable data is being drowned out by “noise”. Furthermore, locating the data of interest can be a needle-in-the-haystack exercise when reports are so large.

Solving the Gray Literature Problem(s)

In 2007, the Maryland Historical Trust (MHT), the SHPO for the State of Maryland, embarked upon an ambitious project aimed at synthesizing the now 53 years of compliance-driven archaeological research conducted within the state since inception of the National Historic Preservation Act. Startup work was funded by a grant from the MHT Board of Trustees, with additional funds coming later via Transportation Enhancement funds administered by the Maryland State Highway Administration.

A major component of the Maryland Archaeological Synthesis Project has been the generation of a searchable database of synopsis reports (think expanded abstract). Additional products will eventually be overview print and other media publications aimed toward the general public. The development of the project database has been focused on providing both the general public and the archaeological community with access to Maryland’s archaeological gray literature data, while simultaneously overcoming the three aforementioned obstacles: the paper backlog, report volume, and site location data.

As mentioned previously, the paper backlog of gray literature reports prior to the outset of the project consisted of some 3,700 gray literature reports for both terrestrial and maritime archaeology undertakings. Early on it was determined that online access to all of these reports was not feasible, nor was it necessary. A majority of these reports are Phase I survey and reconnaissance reports. While clearly valuable data are present, most of the really critical data is replicated in the Maryland Archaeological Site Survey Files that CRM contractors complete when their reports are submitted to the state for legal review and compliance. Sites that had only been subjected to Phase I work were already well represented in MHT’s site files and a separate project was underway to make the site files available to professional archaeologists online (now live). For the Synthesis Project, effort would instead be focused on sites which had been subject to Phase II testing and Phase III data recovery efforts. The much more comprehensive site data in these reports is not replicated in the MHT site files and is also the data that is likely to be of the greatest interest to both academic researchers and the general public.

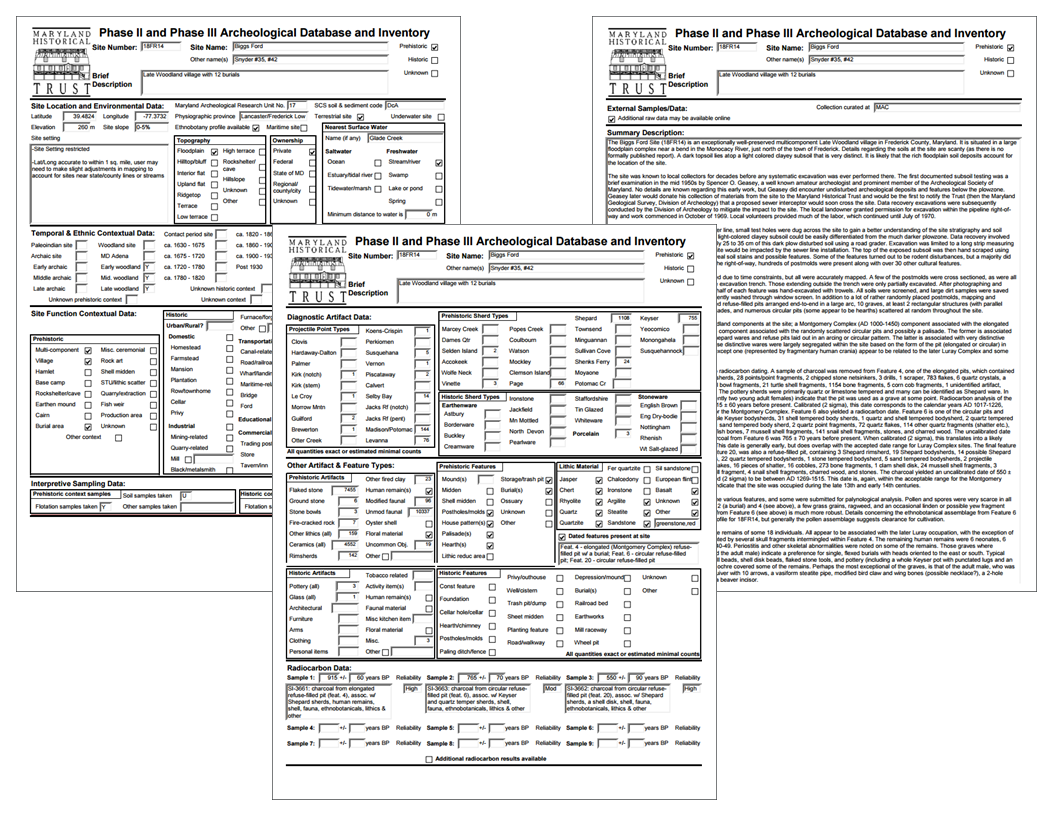

While access to full site reports is desirable for certain purposes (and MHT is working to make that possible), in the interest of data synthesis it is often more useful to start with something smaller. Again, the size of these reports can actually function as a hindrance to conducting research. A researcher interested in any given topic is likely to have dozens of print reports (each hundreds of pages long) to cull through, before winnowing down to the handful of reports in which he or she may actually be interested. While abstracts are helpful, they often do not contain enough data to identify whether or not a particular site report is worth examining further. The MHT’s synthesis project seeks to attain a middle ground by generating “synopsis reports” or capsule summaries that provide a snapshot of the most relevant data (see Figure 1).

A typical synopsis report distills the most relevant data into a manageable, digestible and typically 3-6 page format. The synopsis reports currently in the MHT synthesis database provide an overview of all work conducted at the site (pulled from the original print reports by MHT staff), location and environmental information, and aggregate data tables of site features and artifacts organized in such a way that researchers can quickly pull out the information most relevant for their projects. Data is also pulled directly from the MHT archaeological site survey files to provide more detailed reports. This strategy not only migrates the gray literature data from a paper-based format, but also makes it more digestible. Once the researcher knows which sites are of definite interest, they can then make arrangements to access the full CRM report in the MHT library, and (we hope) eventually online.

Finally, site locations are protected within the Archaeological Synthesis database by providing tiered access to these synopsis reports. Two versions of the database have been made available online: a password-protected version for archaeologists that meet the Secretary of the Interior’s Professional Qualifications for Archaeologists, and an open-access version for the general public. The data available in both versions are identical with the exception of three fields: Site Setting, Latitude, and Longitude. Site Setting for professionals typically provides a brief description of the local environment and often detailed instructions on how to locate the site. Latitude and Longitude represent the centroid of the site area polygon from our in-house Geographic Information System. On the public side of the database, Latitude and Longitude are randomized to within one square mile of the actual site location and Site Setting is entirely restricted. MHT feels that this strategy provides an appropriate compromise between protecting site location information and providing the public with the data collected at their expense.

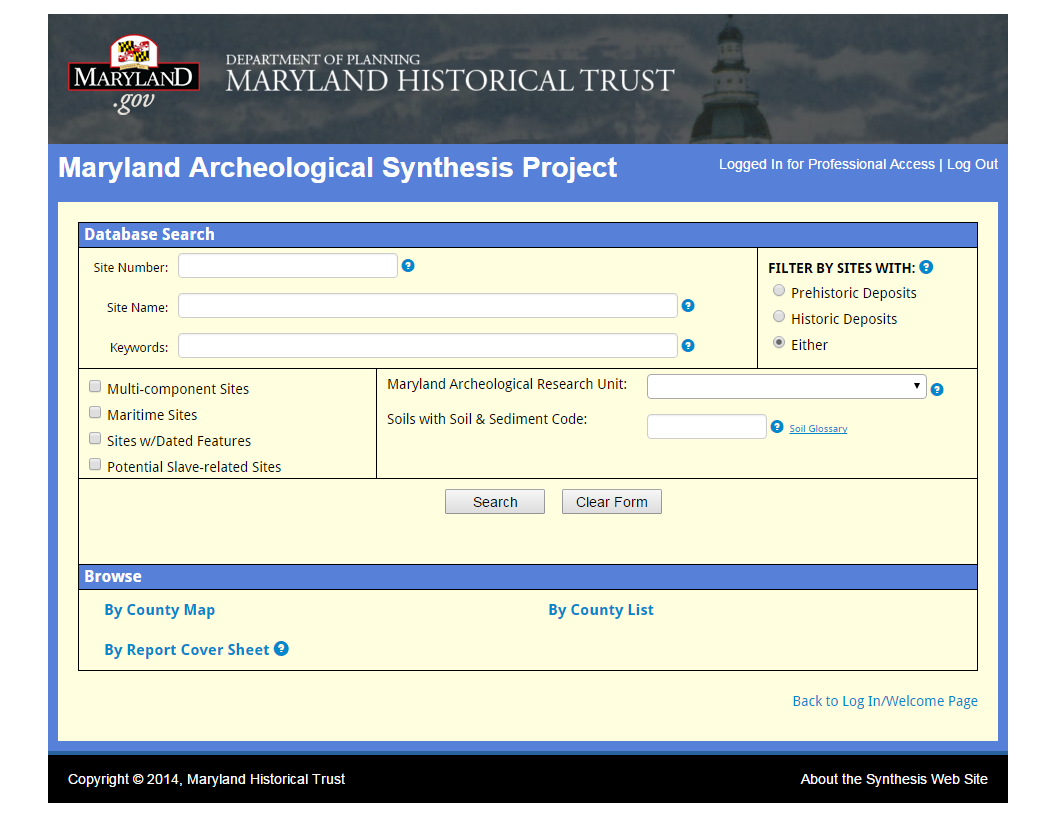

The Archaeological Synthesis Project is online at https://mht.maryland.gov/secure/synthesis/. The synopsis report data is archived in SQL Server where it is keyword searchable via a web interface. Researchers don’t have to have a particular site in mind when performing a search, and thus, their past experience is no longer a limitation to data synthesis. In addition, the database can be queried by site name, trinomial number (or partial number), Maryland Archaeological Research Unit, Soil types, and other variables (see Figure 2). Each query points to any number of “hits”, and each hit points to an URL for the site synopsis report in Adobe PDF format.

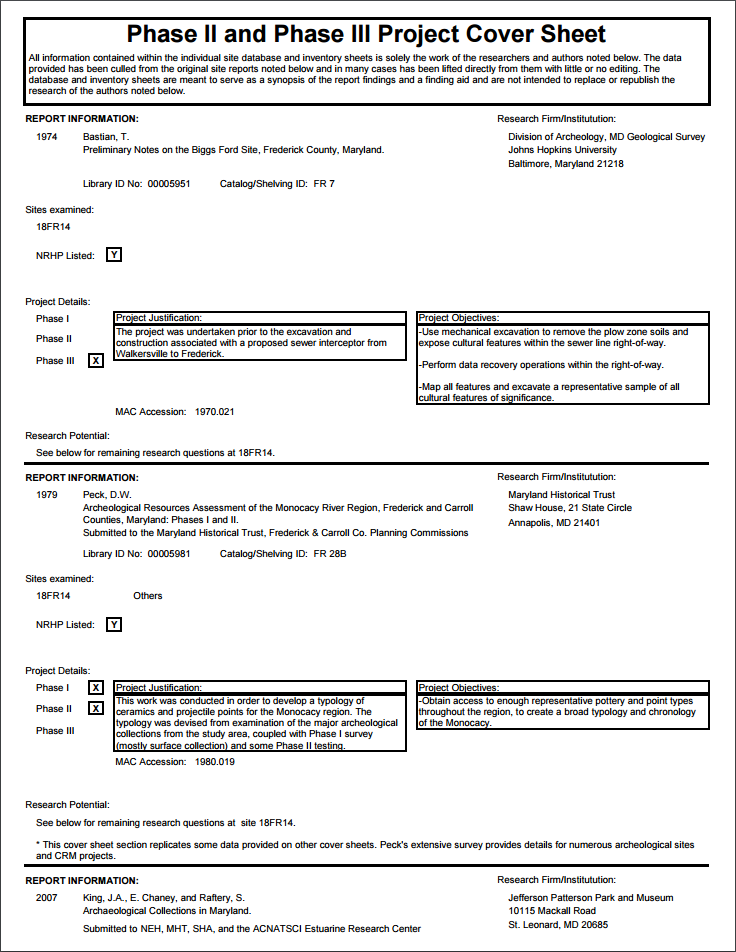

Each hit also points to an URL for a reference cover sheet which is prepared to summarize the various projects (compliance or otherwise) that were responsible for the generation of information on a site or a given group of sites (e.g., highway widening, undergraduate fieldschool, construction of a prison, real estate development, etc.). The project cover sheet summarizes the purpose for the archaeological work undertaken, the archaeological research questions asked, and other useful information. It also provides an assessment by MHT as to whether the site is likely to retain any additional research potential. An example of a typical reference cover sheet is provided in Figure 3.

Outcomes

The Archaeological Synthesis Project went live on the web on Maryland Day (March 25^th^), 2015. Since then, the project has proven its usefulness in responding to the periodic email and phone requests MHT receives from library patrons with specific research topics in mind. According to senior MHT staff, question responses which once would have taken a week or more of library research work to answer, can now be responded to in a matter of minutes. This is over and above the everyday queries that our patrons can now make on their own (again, significantly reducing the workload on MHT staff). In addition, the synthesized data will help redirect future investigations to examine data gaps, provide readily accessible comparative data to enable informed National Register evaluations, and focus research questions to target important issues for data recovery efforts.

MHT’s Office of Preservation Services staff use the database on a daily basis in their review of submitted projects for their impacts on archaeological resources in accordance with both federal and state historic preservation law (Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966 and the Maryland Historical Trust Act of 1985). Through the ability to search the database on a regional or statewide basis and the detailed information presented in the accompanying synopsis reports, staff are able to make informed and justifiable decisions much more efficiently and accurately. The types of decisions routinely made with the assistance of the Synthesis database include the following:

-

determining the level of effort necessary for a given investigation based on results from previous studies as well as data gaps for a particular region, time period or site type;

-

evaluating sites for National Register eligibility & placing them within an appropriate context;

-

identifying relevant research questions to focus data recovery and produce useful results; and;

-

helping to define appropriate mitigation measures (through traditional or creative means) to compensate for adverse effects to a significant site.

One recent example involved a proposed project that had the potential to impact surviving sections of an archaeological site that was originally investigated and partially excavated over 30 years ago. The Birely Tannery site (18FR575) was originally identified during planning for the Carroll Creek flood control project during the 1970s and 1980s, determined eligible for the National Register, and portions of the site were excavated in 1990 prior to its destruction by the flood control project. The data recovery investigations (Thomas et al. 1991) examined numerous archaeological features and midden areas associated with various aspects of the tannery operations during the 19th and early 20th centuries. While portions of the site were destroyed for the flood control project, archival information indicated that the site originally extended beyond the boundaries of that specific project.

When a construction project subject to MHT review was proposed in this area, staff queried the Synthesis Project database to quickly anchor themselves in the archaeological “milieu” surrounding the site. It can be difficult to quickly and efficiently get a handle on past archaeological work at a site, on work at other sites in the region, on sites of comparable research value and interest, and on sites in similar environmental settings without such a tool. The MHT staff quickly discovered that the Birely Tannery site (18FR575) constitutes the sole tannery site in Maryland that has been professionally investigated at the Phase II/III level and found to yield substantive and comprehensive information regarding this important industry throughout the 19th and into the mid 20th century. MHT staff recommended Phase I/II archaeological investigations which revealed Site 18FR575 extended into the impact area for the new construction. The new investigations identified the remains of 13 tannery related features including: four tanning pits, one waste pit, stone paving, and the remains of several structural foundations. The site still contains buried surfaces and features that survive beneath the various fill and disturbance actions that have occurred on the site during the mid to late 20th century. These newly discovered resources represent the site’s continuation into the project area, as expected, and contain an important record of the history, development and operations of the Birely Tannery.

Increasingly, MHT staff are seeing that archaeological consulting firms are making use of the Archaeological Synthesis database to perform background research and inform recommendations. In October of 2017, a Phase II study was carried out at the Jones Farm (18QU1052) in Queen Anne’s County prior to installation of a solar power generation complex (Petyk 2017). The solar installation project was to be located on a tract that was consistently used by tenant farmers, but owned by absentee landlords dating back to at least the last quarter of the 18th century. Ceramics recovered during the Phase II excavations on the farm provided a mean ceramic date of 1802 for the site and also suggested a relatively low economic status for the site’s occupants. The Phase II investigation also identified the presence of an intact feature (likely a cellar) near the center of the site, indicating that the farm retained good integrity and might contain additional features associated with the late 18th to early 19th-century occupation of the property. The Phase II report notes that while, tenancy was a common practice in Queen Anne’s County during the 18th and 19th centuries, examination of the Archaeological Synthesis database revealed this type of site has been largely understudied in the county and throughout the Eastern Shore of the state. No 18th century tenant occupations in Queen Anne’s County have been subjected to Phase II investigations, and only one other site (in Talbot County) has been evaluated at the Phase II level. That site was found to have been heavily impacted by modern disturbances.

Following MHT’s review of these findings and the results of the Phase II background research, staff concurred that site 18QU1052 does indeed possess good integrity and unique research potential and was therefore eligible for inclusion in the National Register. MHT staff also concurred with the recommendation that the site should be avoided during construction and preserved in place, an arrangement that the solar installation firm agreed to. The site was avoided by providing a 30-meter buffer from the site boundary and installing protective fencing and signage.

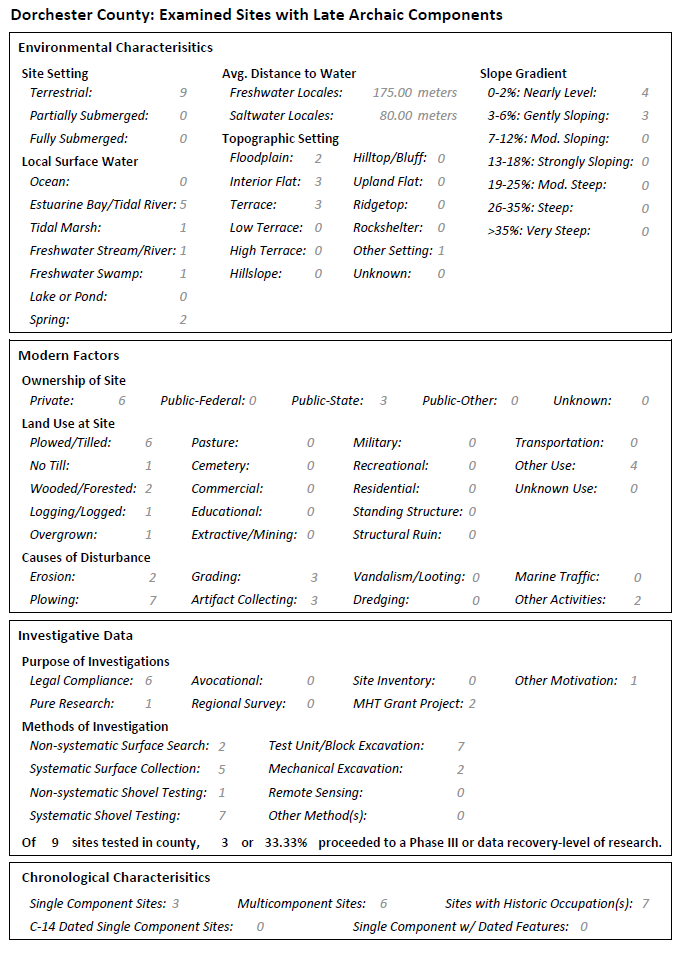

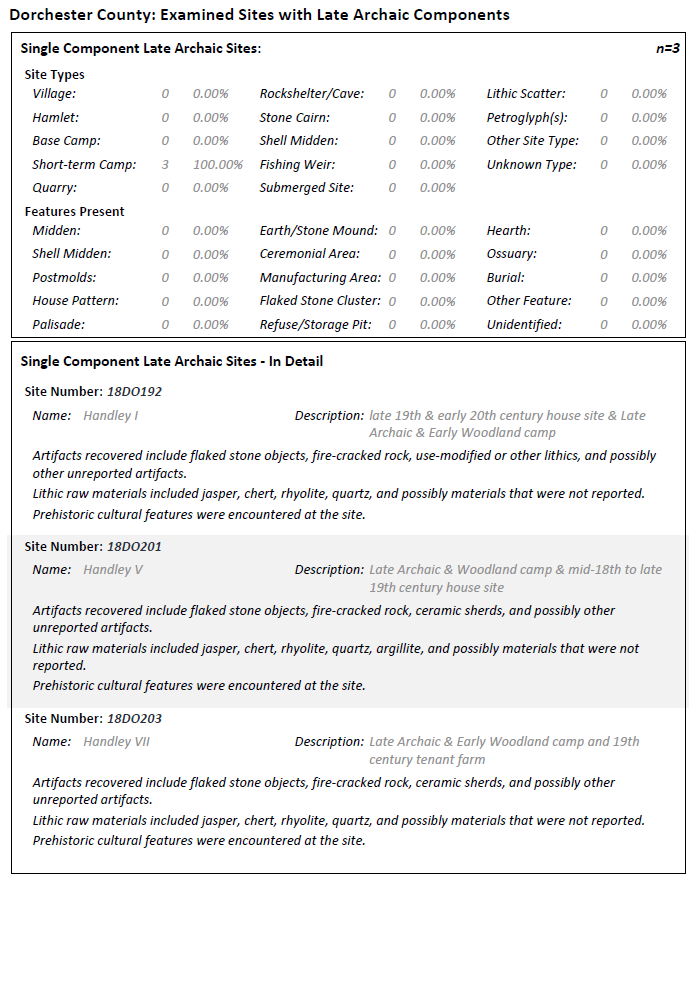

Finally, the Archaeological Synthesis Project is also providing opportunities for MHT staff in the Office of Research, Survey, and Registration to step back and explore data gaps, research priorities, development of predictive modeling, and other topics that they have heretofore been unable to consider. Figures 4 and 5 are from a recent analysis performed on the Archaeological Synthesis dataset to explore sites with Late Archaic components that have been examined at the Phase II or III level. In this case, a report was run to look only at the data from one area: Dorchester County, Maryland. The report could have as easily been run looking at a specific physiographic province, watershed, or a different time period. The point is that the Office of Research now has a tool in place (the Archaeological Synthesis Database) to begin looking at patterns in the data and plan research priorities accordingly.

Conclusion

Gray literature has been vexing to whole generations of archaeologists now that we are 53 years on since passage of the National Historic Preservation Act. That legislation has focused intense time and energy on the collection of data with less attention paid to how that data would be made available so that it could inform decision-making and be interpreted for the public. But innovative new technologies are beginning to bridge the gap between traditional published data sources and less-widely distributed archives of archaeological information.

The Maryland Historical Trust is at the forefront of this innovation, working towards technologies that will permit rapid and ready access to the archaeological information that we have at our disposal. With an eye towards the future, we are attempting to design these technologies in such a way that they can work seamlessly with other innovative projects and as yet unimagined technologies. The end result will be a new era in archaeology where the first true synthesis of all archaeological data, both the research conducted in academia and the tremendous amount of work completed by CRM professionals, becomes possible.

Works Cited

Adelman, Jean, and Eileen Markson 1987 Archaeology Resources in Libraries: Are they Accessible? Art Libraries Journal 12(4): 31-35.

Alberani, Vilma, and Paola De Castro 2001 Grey Literature: from the York Seminar (UK) of 1978 to the year 2000. INSPEL 35: 236-247.

Archaeology Data Service (ADS) 2018 Background and ADS Library Statistics. Archaeology Data Service, University of York, York, UK;http://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/about/; and http://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/library/admin/statistics.xhtml;. Accessed 16 March 2018.

Bradley, Richard 2006 Bridging the Two Cultures – Commercial Archaeology and the Study of Prehistoric Britain. The Antiquaries Journal 86: 1-13.

Brin, Adam 2018 Looking Back at 2017, Part II: tDAR, Content, and Usage. The Center for Digital Antiquity, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ ;https://www.tdar.org/news/2018/01/looking-back-at-2017- part-ii-tdar-content-and-usage/;. Accessed 15 March 2018

Carnett, Carol 1991 Legal Background of Archeological Resources Protection. National Center for Cultural Resources - National Park Service, Technical Brief, No. 11. Washington, DC.

CAST and NPS 2015 National Archeological Database (NADB). Archeology Program - National Park Service, Washington, DC ;http://www.nps.gov/archeology/tools/nadb.htm;. Accessed 14 December 2015.

Childs, S. Terry, and Eileen Corcoran 2000 Managing Archeological Collections: Technical Assistance. Archeology Program - National Park Service, Washington, DC ;http://www.nps.gov/archeology/collections/;. Accessed 14 December 2015.

Cohen, David J., Robert E. Murowchick, and Jeffrey Y.T. Kao 2018 ARC/Base: A Comprehensive, Multilingual, Web-based Bibliographic Database for East Asian Archaeology. International Center for East Asian Archaeology and Cultural History, Boston University, Boston, MA ;http://www.bu.edu/asianarc/projects/arcbase/slideshow/;. Accessed 15 March 2018.

Denda, Kayo 2002 Fugitive Literature in the Cross Hairs: An Examination of Bibliographic Control and Access. Collection Management 27(2): 75-86.

Digital Antiquity 2018 About Digital Antiquity. Digital Antiquity, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ ;http://www.digitalantiquity.org/about/;. Accessed 15 March 2018.

Harrison, John 2005 Grey Literature or Fugitive Report Project. MLA Forum 4(1).

Jones, Siân, Ann MacSween, Stuart Jeffrey, Richard Morris, and Mike Heyworth 2001 From The Ground Up: The Publication of Archaeological Projects, a User Needs Survey. Council for British Archaeology, York, UK.

Kansa, Eric 2005 A Community Approach to Data Integration: Authorship and building meaningful links across diverse archaeological data sets. Geosphere 1(2): 97-109.

Kintigh, Keith 2006a The Promise and Challenge of Archaeological Data Integration. American Antiquity 71(3): 567 578.

Kintigh, Keith 2006b The Challenge of Archaeological Data Integration. Paper presented at the meeting of the Union Internationale des Sciences Préhistoriques, Lisbon, Spain.

Kintigh, Keith, Jeffrey H. Altschul, Ann P. Kinzig, W. Frederick Limp, William K. Michener, Jeremy A. Sabloff, Edward J. Hackett, Timothy A. Kohler, Bertram Ludäscher, and Clifford A. Lynch 2014 Final Report of the Workshop - Cultural Dynamics, Deep Time, and Data: Planning Cyberinfrastructure Investments in Archaeology. Final report of a workshop held February 7^th^ and 8^th^, 2013, National Science Foundation, Arlington, VA.

Lattanzi, Gregory D 1999 Cultural Resource Management and the Internet: A Touch of "Gray". The SAA Bulletin 17(4): 30- 33.

Lawrence, Amanda, John Houghton, Julian Thomas, and Paul Weldon 2014 Where is the Evidence? Realizing the Value of Grey Literature for Public Policy and Practice. Swinburne Institute for Social Research, Melbourne, Australia.

Museum of Underwater Archaeology (MUA) 2018 Gray Literature Bibliographic Database. The Museum of Underwater Archaeology; http://www.themua.org/collections/items/browse?collection=10;. Accessed 15 March 2018.

Owen, John Mackenzie 1997 The Expanding Horizon of Grey Literature. In GL3 - Third International Conference on Grey Literature, pp. 1-5. 2005, pp. 194-203. Luxembourg.

Petyk, Richard 2017 Technical Report: Phase II Archaeological Testing at Site 18QU1052, Jones Farm E, Jones Farm Solar Project, Queen Anne’s County, Maryland. GAI Consultants, Inc. Warrenton, VA.

Rivers Cofield, Sara, and Jodi Reeves Flores 2014 Evaluating a Cooperative Approach to the Management of Digital Archaeological Records. Department of Defense Legacy Resource Management Program, Project No. 13-711. Washington, DC.

Schöpfel, Joachim 2006 Observations on the Future of Grey Literature. The Grey Journal 2(2): 67-76.

Seely, Amber 2005 Digging Up Archaeological Information. Behavioral and Social Sciences Librarian 24 (1): 1-20.

Snow, Dean R 2010 Making Legacy Literature and Data Accesible in Archaeology. In Proceedings of the 37^th^ International Conference on Computer Applications and Quantitative Methods in Archaeology, B. Frischer, J. Webb Crawford and D. Koller, editors, pp. 350-355. Williamsburg, VA.

Snow, Dean R., Mark Gahegan, C. Lee Giles, Kenneth G. Hirth, George R. Milner, Prasenjit Mitra, and James Z. Wang 2006 Cybertools and Archaeology. Science 311(5763): 958-959.

Stock, C., and J. Schöpfel 2003 Grey Literature in an Open Context: From Certainty to New Challenges. In GL5 – Fifth International Conference on Grey Literature, pp. 1-1. Amsterdam, Netherlands.

Thomas, Ronald A., Merle Dunn, Kathleen Ryan, Domenic Seguto, R. Bruce Hoadley, Kenneth Baumgardt, and Robert F. Hoffman 1991 Phase III Data Recovery at the Birely Tannery (18FR575), City of Frederick, MD. MAAR Associates, Inc. Newark, DE.

Warnick, Walter 2001 Tailoring Access to the Source: Preprints, Grey Literature and Journal Articles. Nature – Web Debates. Published May 3, 2001. ;http://www.nature.com/nature/debates/e-access/Articles/ warnick.html;. Accessed 23 December 2015.

Figure 1: Screenshots of a Typical Synopsis Report

Figure 2: Screenshot of the Searchable Web Interface

Figure 3: Screenshot of a Typical Reference Cover Sheet

Figure 4: Database Report – Analysis of Late Archaic Sites in Dorchester County, MD (Page 1)

Figure 5: Database Report – Analysis of Late Archaic Sites in Dorchester County, MD (Page 2)