Managing Digital Data at the North Carolina Office of State Archaeology: Challenges and Directions

The North Carolina Office of State Archaeology (OSA) was created by the North Carolina General Assembly in 1973 to coordinate and implement a statewide archaeological preservation program. This program includes prehistoric, historic, and underwater archaeology, and is implemented by staff in five offices throughout the state. Central to this program is the OSA’s management of records, including those documenting the more than 50,000 archaeological sites located in the state’s 100 counties, and a library of nearly 8,000 associated reports. The OSA Research Center curates hundreds of thousands of artifacts and their associated records from across North Carolina.

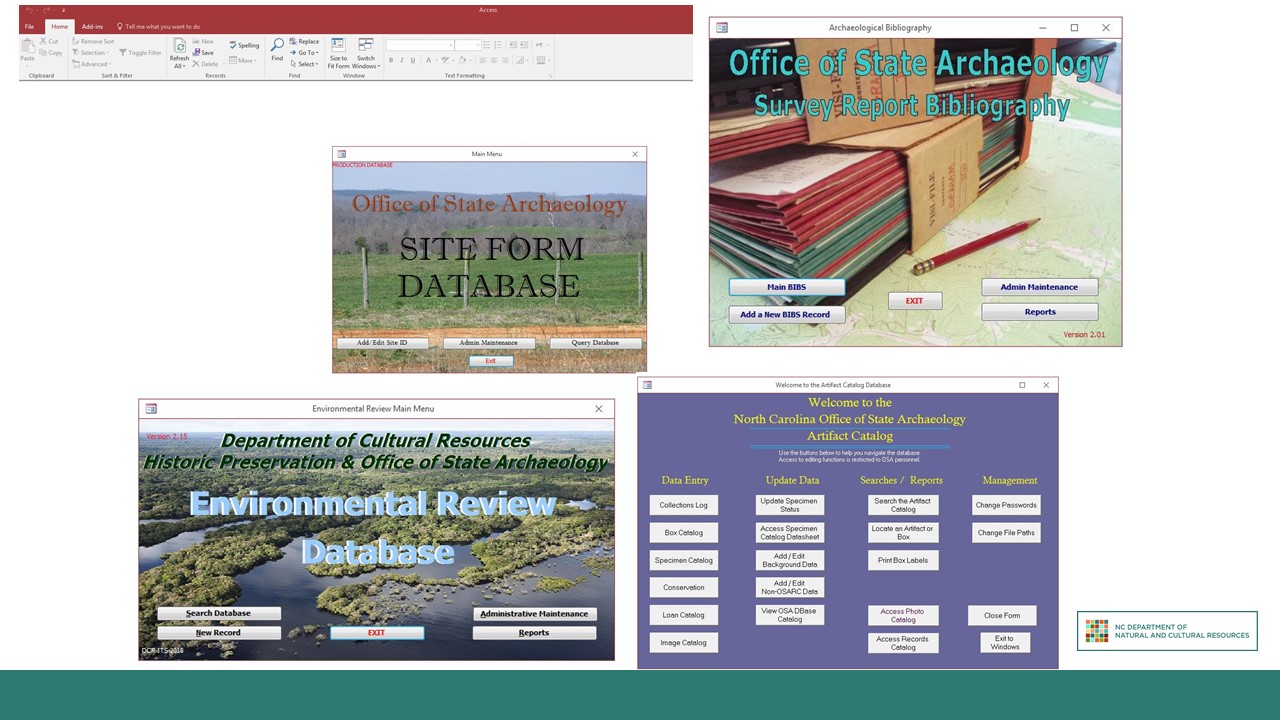

While there are computer databases for the site forms, bibliographic entries, environmental review projects, maps, and artifacts, there is variability in the extent to which all records have been added to these databases. In some cases, it is difficult to estimate how much remains undigitized. Arduous and labor intensive, the process of digitizing our records has evolved with the available technology and been limited by staffing. Our goal is to have this data in GIS and electronic databases accessible to researchers and easy to query. We will discuss our efforts to reach this goal and the potential benefits of digitizing our records.

Current State of OSA Records

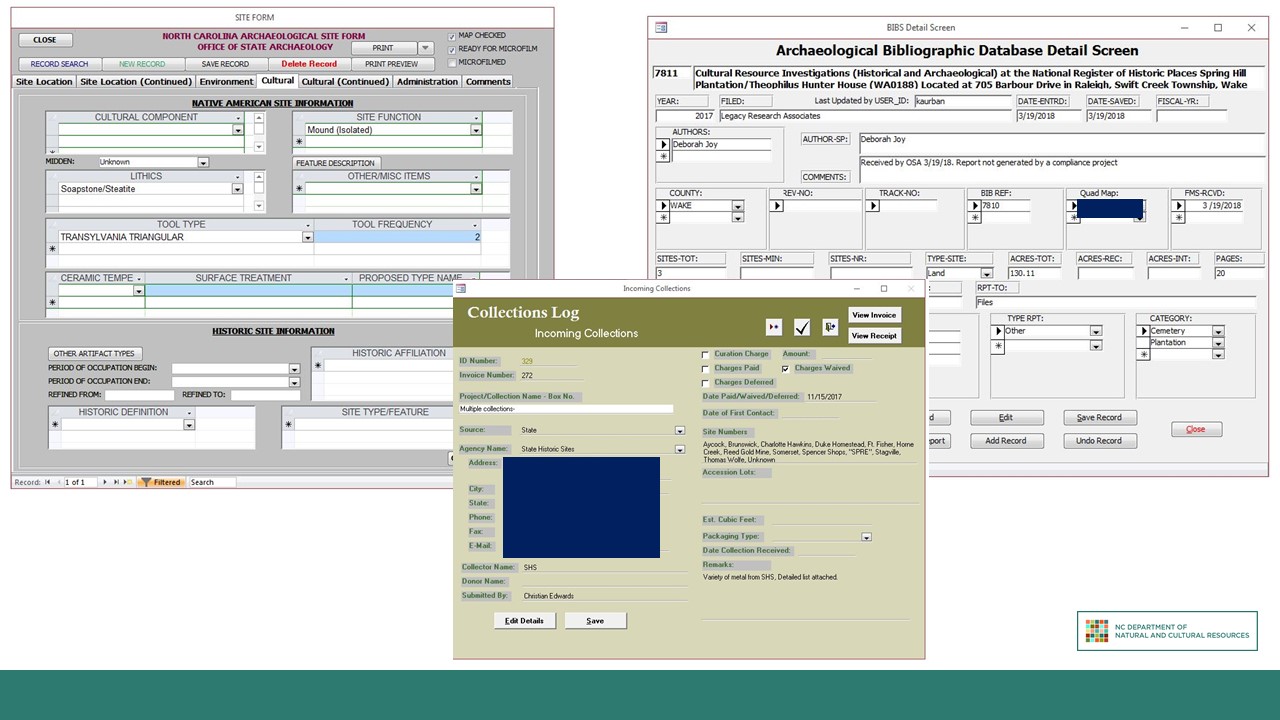

Currently, the NCOSA uses four databases created in Microsoft Access: site forms, survey report bibliography, artifact catalog, and environmental review projects. All four databases were created within the last 10 to 20 years by Department of Natural and Cultural Resources IT employees or contractors and can only be changed by IT staff. The relatively old age of the databases and the lack of administrative access are two of the most immediate problems with our system.

Each of the four Access databases vary in the degree to which they meet our ultimate goal having of accessible and easy-to-query data repositories. The site forms database allows us to enter information on many aspects of archaeological sites (including environment, location, National Register status, and types of artifacts) into separate fields. However, the database only allows users to query based on specific site numbers. You can look up a particular site you are interested in if you know its trinomial designation; however, you cannot search for all sites with Middle Archaic points or all sites on a particular topographic quad map.

The survey report bibliography database does allow you to search based on a variety of factors, including report number, author name, county, and year. It is useful for finding bibliographic information about reports and for searching for all resources on a specific topic, in a certain area, or so forth. The artifact catalog also has better search functionality, but can still be difficult to navigate without already knowing site and accession numbers.

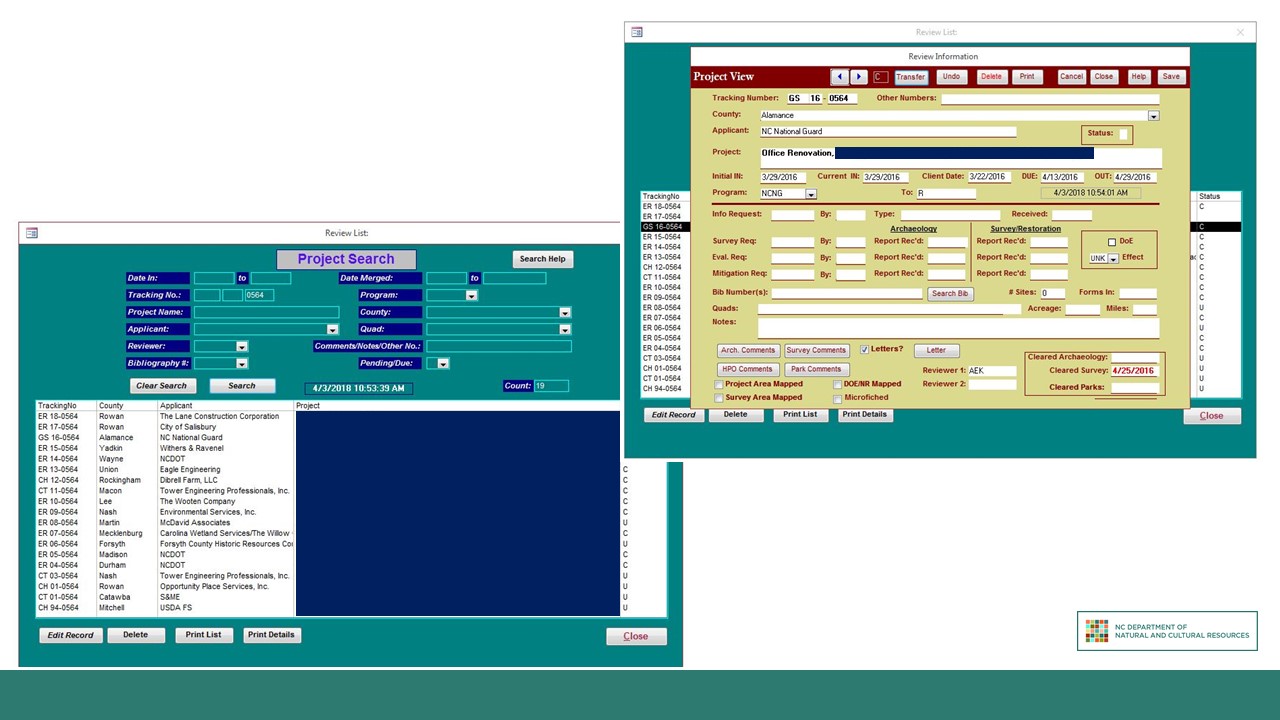

The environmental review database is our final Access database. It was preceded by a DOS-based system, which replaced typed index cards. It is used by the NCOSA and the NC Historic Preservation Office (HPO) to log, track, and review any ground-disturbing projects on state or federal land or using state or federal funds, grants, or permits to assess the likely impact on cultural resources. The environmental review database allows users to search for projects based on numerous criteria and enter pertinent data into multiple fields. It is the only one of our databases that allows users to upload and attach files to the records. This function has only been employed for less than five years, and is managed by the HPO. The ability to attach related files is something that would be very useful for our databases: to attach pdfs of reports to their bibliography entry, maps and artifact catalogs to their site form entry, and pictures to artifacts. Unfortunately, when the databases were created only the environmental review database was programmed to allow this function, and we have been unable to change the other systems in the intervening time.

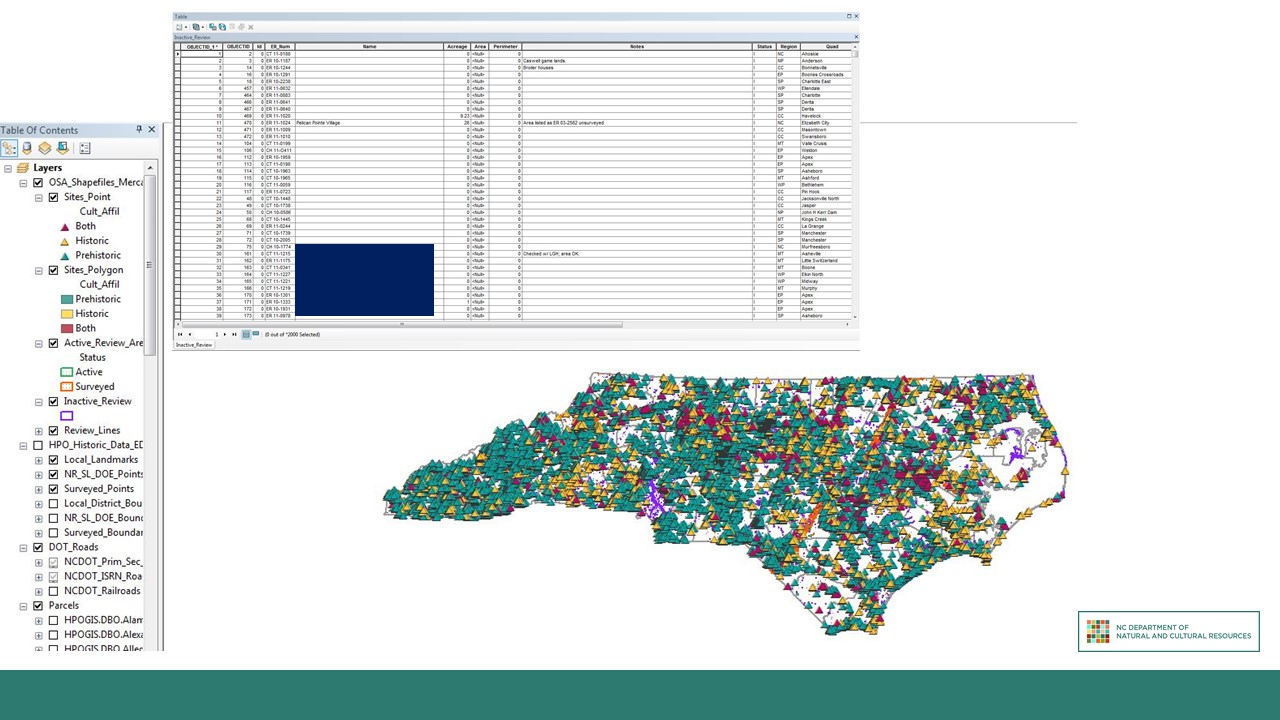

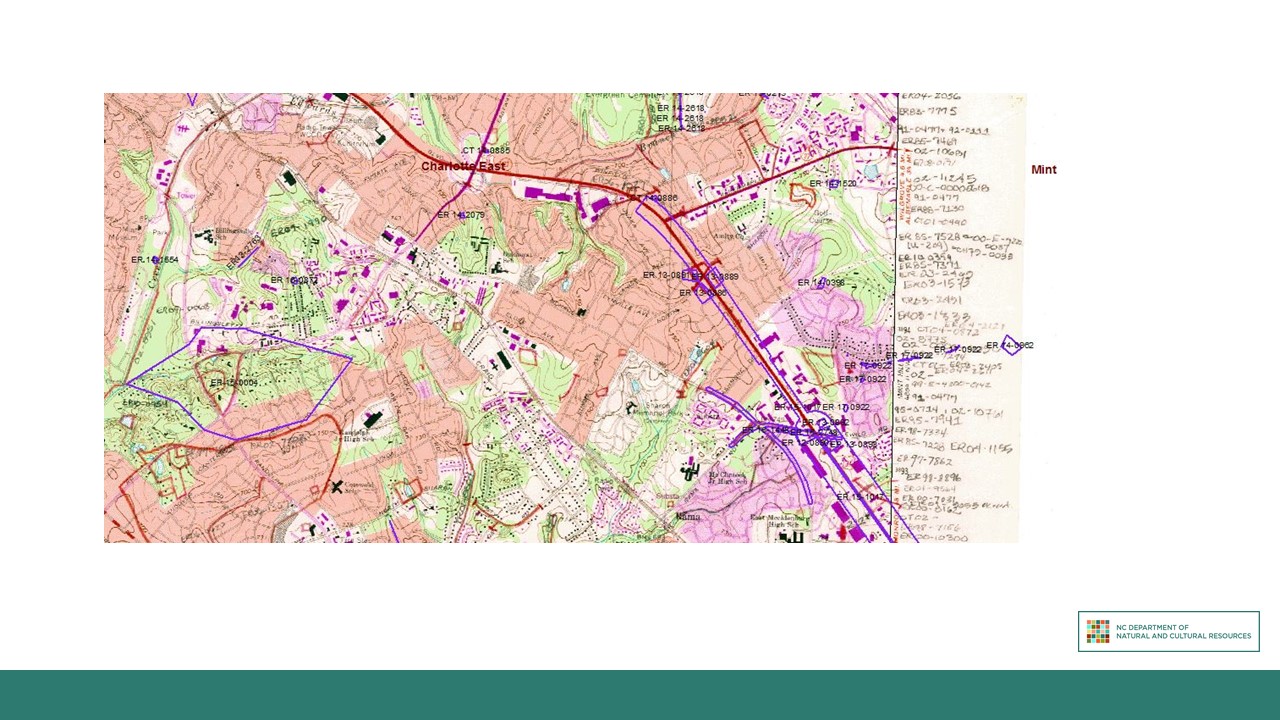

In addition to the four Access databases, we maintain a GIS database of sites and projects throughout the state. This is by far our most “modern” database, and because it is administered by the NCOSA’s GIS specialist, it is also the one over which we have the most control. Starting in 2011, every newly reported site and environmental review project area has been mapped in to GIS as soon as our office received it. The attribute tables for site and review features provide pertinent information on the projects, giving a quick snapshot of the record. Prior to 2011, all sites and projects were drawn on USGS topographic quad maps. The picture on this slide shows what those records look like: features were drawn on with red pencil, site numbers were written next to sites, and project numbers were written in the margins of the maps. The quad maps have been scanned and added to GIS, and many of the features from those maps have been drawn into GIS and added to the attribute tables, making them searchable.

Challenges and Directions

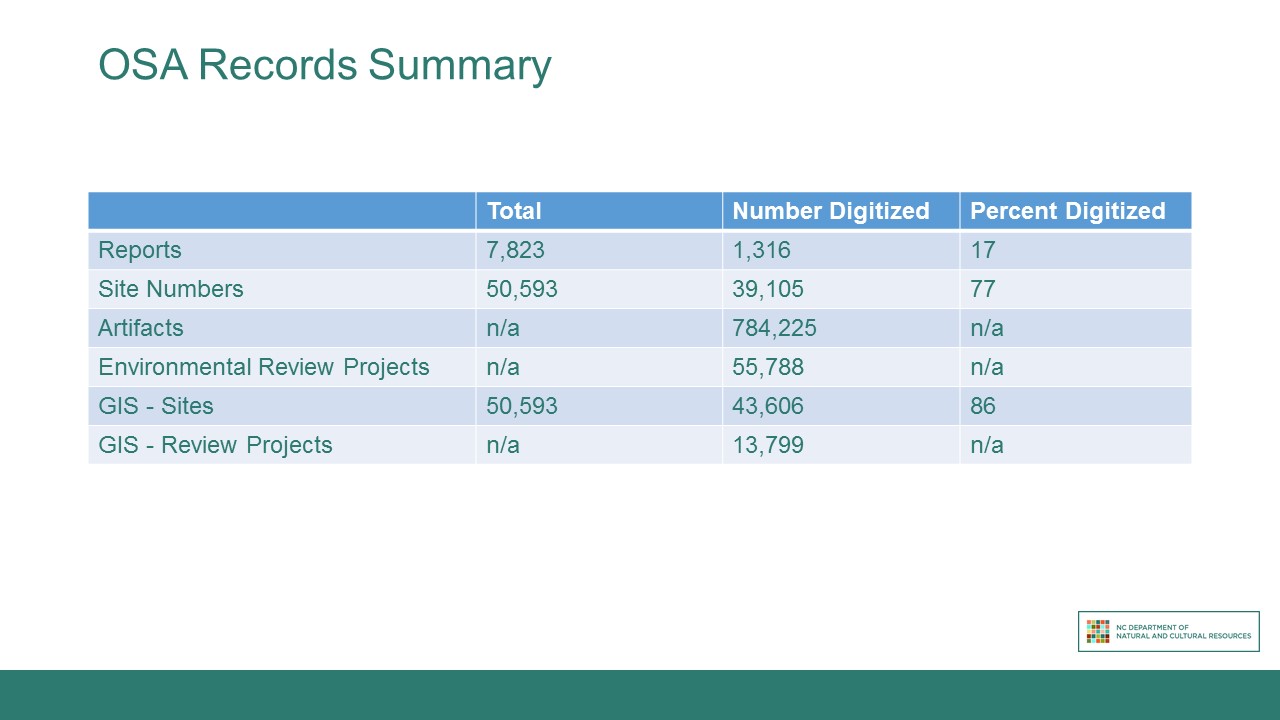

I attempted to create a summary of our records statuses to show our digitization progress, but for some categories it was difficult to even quantify how much we are missing. Reports are the most straightforward category – we have 17 percent of our report library in an electronic form. These reports are hosted on an office server. For site numbers, we know that we have assigned 50,593 trinomial designations and that we have entered 39,105 site forms into our database (77 percent of our records digitized). However, our underwater archaeology endeavors are not accounted for in these numbers. When the NC Underwater Archaeology Branch was first established, it started using its’ own site naming convention for underwater archaeological resources based on the body of water in which they were located, rather than by county. Of the approximate 1,000 underwater sites the OSA has recorded, only about five percent have trinomial designations. The remaining 95 percent are mostly unaccounted for in the NCOSA database because the format of those records is not well-adapted to our terrestrial site form database. While our site form has been edited to include fields pertinent to underwater sites, we do not have the administrative ability to change our electronic database to accommodate these additional data fields.

The artifact catalog has entries for almost 800,000 individual artifacts, but there are older collections at our research center that have not been inventoried and entered into the database. We cannot say what percentage of our artifacts are accounted for digitally. We have a similar problem with the environmental review database. The database was created in 2000 to replace a DOS-based version. Some records from the previous decades of environmental review were added to the digital database, but not all. Many of the older records in the database do not have supporting documents attached to their file. Tracking down the physical copies of those supporting documents can be challenging, but occasionally necessary. While many of the projects reviewed by the NCOSA are cleared without comment, some take a long time to be completed and must be revisited decades after the initial request for review. Our office recently reviewed an airport project that was started nearly 30 years ago and needed a comprehensive understanding of the project history to best advise the involved parties. In cases like this, easy-to- find and access records are integral to our decision-making process.

There are many challenges to accomplishing these goals, including some all-too-common problems and some that are unique to our organization. The common problems include limited staff hours and lack of funds for better database software. Ever-changing data storage standards and practices have resulted in multiple potential locations for any given record, and can make it difficult to unify all those records in one place. For example, some of our earliest site forms were converted to microfiche by the State Record’s office. Later site forms were scanned by Records and returned to our office as TIFF files on CDs. Of the more recent site forms, some have been electronically submitted or scanned as pdfs by our office and added to the office server, while others remain in paper form only. The result is that anyone interested in seeing data on a specific site can start with the site forms database and may be able to find the information they need. However, if they are looking for one of the 11,000+ site forms that have not been data-entered, or if they need to see associated maps or artifact catalogs, they will have to use the microfiche reader, look through a binder of CDs, or search through boxes of paper copies to find the information they need. The challenge of navigating the numerous records systems has been exacerbated over the past several years, as many people who worked at the NCOSA for decades are now retiring. Those of us who are newer to the organization must try to record the institutional knowledge held by these staff members so that we do not completely lose track of necessary information.

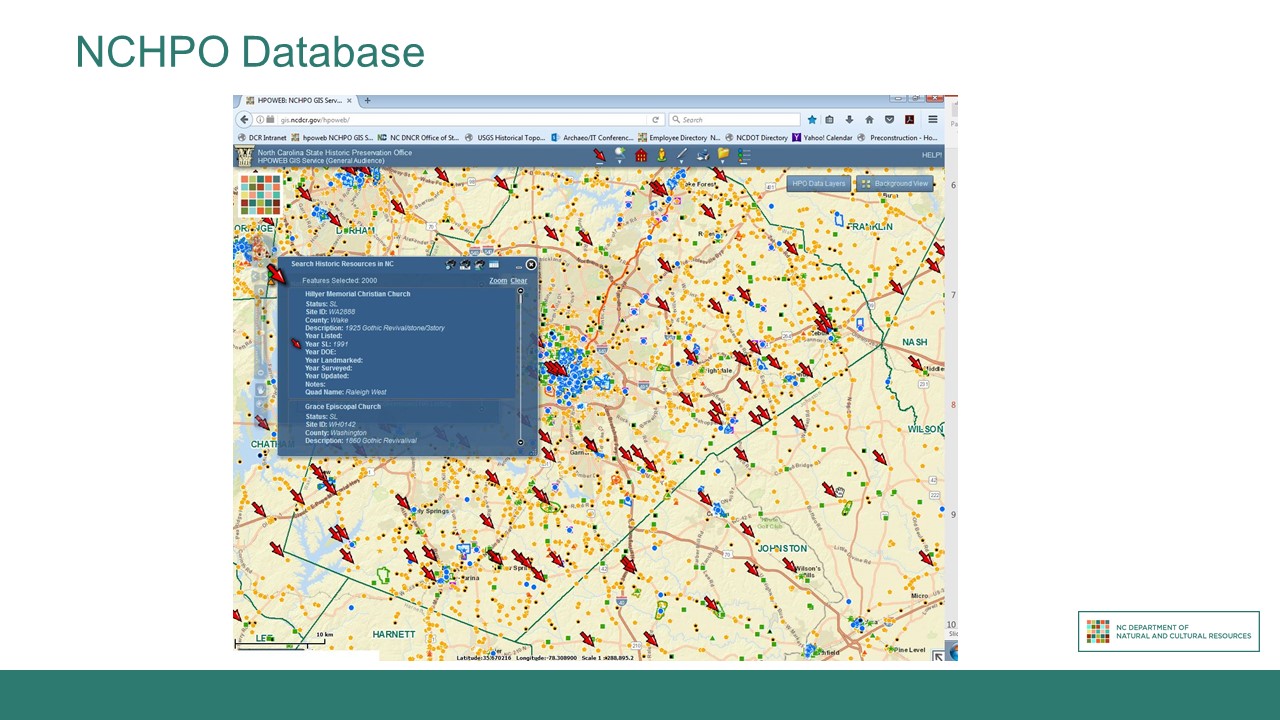

An additional challenge is creating a way for people to remotely access our data. Presently, any researcher looking for information curated by NCOSA must physically come to one of our offices to use our databases. The NCHPO does have an online map of their records created in Adobe Flash (pictured on slide), but we have additional privacy and security concerns that make it more difficult to implement such a service. We know that some states offer remote access to their files, and we would like to be able to do the same. However, we do not have the funds necessary to create and implement an online database with appropriate privacy protections, nor can we charge a fee for that service. Charging a fee, as some other states do, would provide us with funds to implement and maintain such a database, but to accept money for that service, we would have to request a change to the state administrative code - a long and difficult process.

Conclusion

The NCOSA has done a great deal of work already to make our records well-organized and useful to researchers, but we still have a lot left to do to reach our goals for our data repositories. Constantly changing technologies and curation standards make it particularly challenging to keep our digitization efforts current. We are looking to collaborate with other organizations and departments, such as NCDOT, where possible to make our data more accessible to those who need it.