Always Halfway There: Keeping Up with Digital Archaeological Data in Virginia

Since being one of the first State Historic Preservation Offices to adopt electronic records management in the late ‘80s, the Virginia Department of Historic Resources has worked through several iterations of databases and web applications. These systems manage basic site information, details about physical collections, and now digital media and datasets themselves. Over time, the agency’s priorities and objectives surrounding digital records and data have evolved in ways common to other institutions. As the most recent web GIS and database application reaches mid-life after four years, a thorough assessment of current and ideal approaches to digital data curation, preservation, and distribution is coming due as planning begins for what comes next. Building from concepts in libraries and archives, informatics, and data science, this presentation explores possible road maps.

I’m Jolene Smith. Since 2008, I’ve managed archaeological sites data at the Virginia Department of Historic Resources (DHR), the State Historic Preservation Office (the SHPO). In Virginia, we’ve got about 45,000 sites recorded in the statewide inventory, with more added every day that I’m at my desk. This presentation is from my perspective at DHR, but it doesn't necessarily reflect the priorities of my agency as a whole.

We the site file managers are Maintainers. Few, if any, of us are formally trained in library science, archives, or database architecture. Mostly, we seem to identify as archaeologists, even if it’s been a while since we’ve sunk our trowels into soil. The archaeological data that we ingest, curate, and preserve are extensions of the physical, material record.

The nature of our work is that it's never done. We're adding new data and looking for novel ways to organize and use it, but we're also in a perpetual state of organizing, tidying, aligning, and adapting our collections.

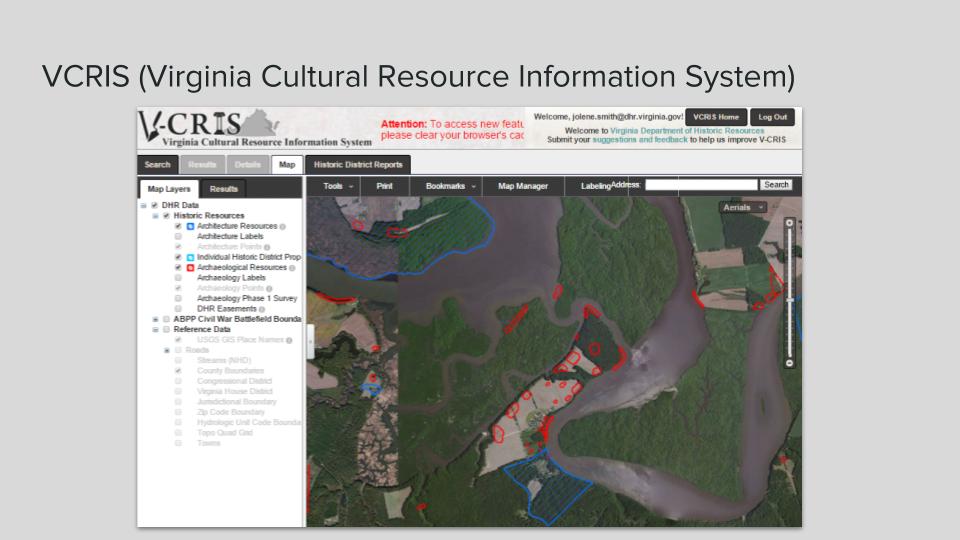

Our voluminous archaeological sites dataset is only part of the story. In the Virginia Cultural Resource Information System (our online inventory database), we've got another 200,000 "architectural" records.1 The archaeological and architectural records are like apples and oranges, and VCRIS is the fruit basket. This presentation is about archaeology, but this kind of context is helpful for understanding.

Where We've Been

While most systematic data collection began with the passing of the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966 and the establishment of the Virginia Historic Landmarks Commission (which would later evolve into the Virginia Department of Historic Resources), the first "official" archaeology records in Virginia were created through the State Library. In 1927, the Virginia State Commission of Conservation and Development established the Division of History and Archaeology. Shortly thereafter, division member E.B. Sacrey established the Archeological Society of Virginia (2004 Library of Virginia). In 1962, the State Library appointed Howard MacCord the first State Archaeologist (2009 Council of Virginia Archaeologists). All this is to say we've been amassing archaeological information through state government for quite some time here.

In the 50 years since the advent of the State Historic Preservation Office (SHPO), we've seen tremendous change, both in volume of records and in technology to make them accessible. In Virginia, records for archaeological resources are managed along side records for above-ground architectural properties. Today, our collection includes about 45,000 archaeological records and 200,000 architectural records.

In 1991 the agency began using IPS (Integrated Preservation Software), an offline relational database developed with the National Park Service and distributed between individuals and institutions and then manually synced as needed. For the first time, archaeological site records were digitized, although only new work. NPS encouraged new kinds of multi-state analysis and new ways to use information and envisioned large-scale data analysis possibilities using a standardized system (Miller 1994), however IPS did not become widely adopted across states (Smith 2016).

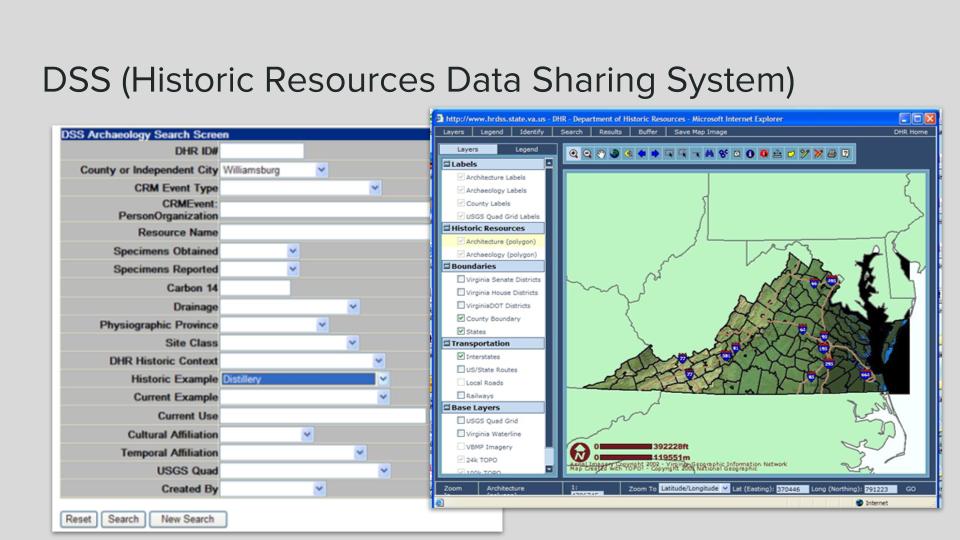

Between the late 1990s through early 2000s, DHR staff and contractors transcribed all basic site-level information from paper records and migrated IPS data into the new Historic Resources Data Sharing System (DSS), one of the first web databases in the country with comprehensive state archaeological site data. For the first time, users had access to statewide information with querying power and a full web GIS.

As our technological infrastructure reached the end of its supported life, we began the process of building a completely new custom application through a vendor, VCRIS (the Virginia Cultural Resource Information System). As part of the development process, we re-modeled data structures and migrated terms. In 2013, DHR deployed the system with a new, more powerful web database and map.

What worked:

Geospatial ingest directly from users (resulting in no more hours of heads-up digitizing graphic maps on my part) and strict data entry conditions dramatically improved many parts of our records management workflow. An ESRI feature service allowed us to reduce distribution of static geospatial data, a security risk and an invitation to make mistakes with old data. Tiered access to the system allowed for differential access (data entry, just architecture, or both archaeology and architecture), enabling us to keep a tighter handle on sensitive site locations.

Room for Improvement

Our initial vision aimed for a system that would allow for much more internal collaboration by DHR staff, a goal that was only partially realized. In the old way, the flow of information tends to come in for the most part from outside consultants and Archives staff quality control and maintain the data. We've not yet succeeded in integrating key pieces of management information like National Register eligibility concurrence as it's created.

We initially planned on integrating "file attachments" into each record, to contain digital media related to each site and property. However, some introspection and research into digital preservation and assets led us to the conclusion that we needed to slow down and consider more robust infrastructure for our digital archives in general.

We continue to grapple with data migration issues originating from transcription and transformation between several different databases over decades. For example, we discovered that, for archaeological records in DSS, the reports made certain fields appear related, when in fact there was no true relationship in the database. Some of this cleanup we can do programmatically, but many relationships are highly subjective and require an expert decision to make a site classification or cultural affiliation. All of this makes querying from the front end very difficult (or misleading), and is compounded by some major deficiencies in the query interface.

VCRIS was developed according to a waterfall model of project management. While the philosophy aligned well with government procurement processes, it made iterating through rough spots and making improvements nearly impossible. We are five years into the use of this system and we still have hundreds of items on our "fix" list. However, we changed gears, using an agile approach and are adapting contract schedules to tie into bite-sized goals.

We've also got voluminous collection of media, in various states of digitization. Many photos, slides, and reports have been scanned, but not all. Some were scanned long ago at a resolution that's no longer adequate. Key metadata are stored in filenames in a standardized format, but only to a very low level of detail. We've got some major digital archives work to do.

/box of legacy media photo/

The next thing

Until recently, those of us on the VCRIS team still felt like it was relatively shiny and new. And then a developer broke the news that our baby was officially middle-aged. After we spat out our coffee, we immediately started planning for what is to come.

Of critical importance moving forward for our agency and others is to begin to explode the data silos that we all maintain. Research information, catalogs of our physical collection containing ~8 million artifacts, management and regulatory actions, tracking of preservation easements, and other data produced and maintained between divisions needs to be interoperable and connected. But should we invest in One Application to Rule Them All?

I argue that it might not be a great idea. Funding is often tied to a fiscal year and can be unpredictable from one year to the next. This makes taking on a huge, integrated project a risky endeavor for a small public agency. From a technical standpoint, adopting independent but connected platforms that allow for pragmatic mix-and-match of open source, proprietary "off the shelf," and custom solutions can get us far. We operate in a low-resource environment. Budgets are always tight and access to I.T. expertise can be hard to come by. By being realistic about this from the outset, we can create more durable and flexible systems.

Digital media preservation and access

Development of a digital media repository is a top priority for the very near future. Like many other agencies, undoubtedly, collection of digital media has been a secondary endeavor. We're just now reaching a juncture where most of what we take in is "born digital" and not a scanned surrogate of a hardcopy object. As archives paraprofessionals, we've been working hard to obtain solid knowledge and understanding of digital preservation and access concepts to bring us up to speed.

Competing priorities or a false dichotomy?

At the beginning of any planning and development process, we have to figure out what our applications need to do. What functionality serves our mission? What's very interesting, but probably out-of scope? While budgetary concerns and scope creep are very real, I think it is important to address the notion that creating a powerful archaeological data research tool is somehow at odds with building a great system for managing cultural resources on a more administrative level. When archaeologists (whether commercial or academic) search for information in our inventory of 45,000 sites, they're expecting data that's to some degree comprehensive. Unfortunately, data from some of the most important sites in the Commonwealth investigated outside of any regulatory processes have often fallen through the cracks. Hundreds of theses, dissertations, and academic publications have no doubt created typologies and identified patterns that have not made their ways back to DHR's inventory. And this all has a recursive impact on CRM and agency decision-making. How can we effectively understand a site's significance or rarity if its connections remain unrecorded (or under-recorded)? Research and management are interconnected. Respecting both priorities will elevate the discipline as a whole.

Open data and interoperability

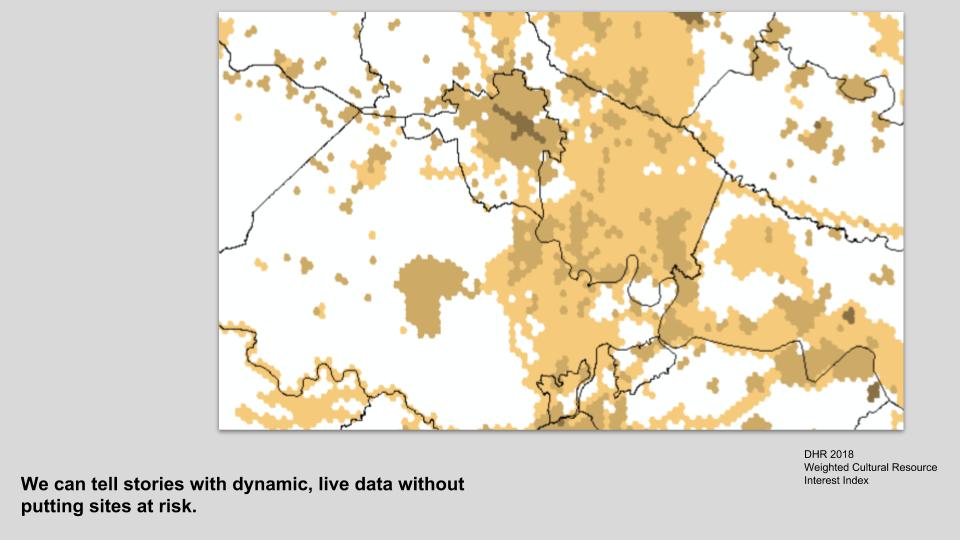

In addition to facilitating good research within and beyond our agency, we need to use our data for outreach in many different ways, and it's not always easy. Archaeological data come with a caveat: locational information and details about the specific nature of certain sites may be very sensitive and protected under state or Federal law. In the past, many SHPOs, including mine, have taken a relatively conservative approach to releasing any data to the public. But not all data are sensitive. By consciously arranging our archaeological data in a way that allows us to protect what's vulnerable and release what's not, we can build flexible new tools for outreach, planning, management, and research.

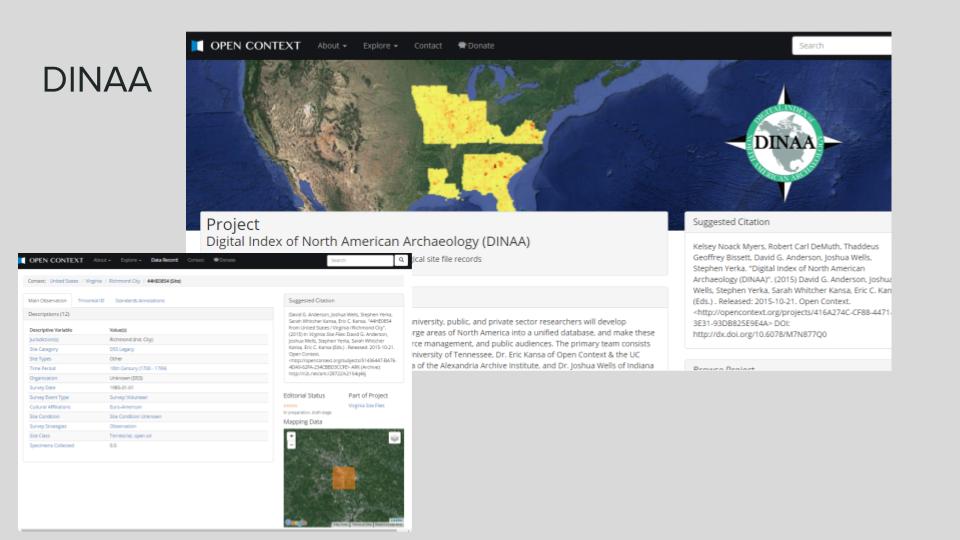

Since 2013, our archaeological data has been a part of the Digital Index of North American Archaeology. Having our data available at a safely publishable scale has been exceptionally fruitful for outreach and interpretation. Since DINAA has already done the work of representing the data in interoperable ways, we've been able to use it again ourselves for multiple purposes through the SHPO.

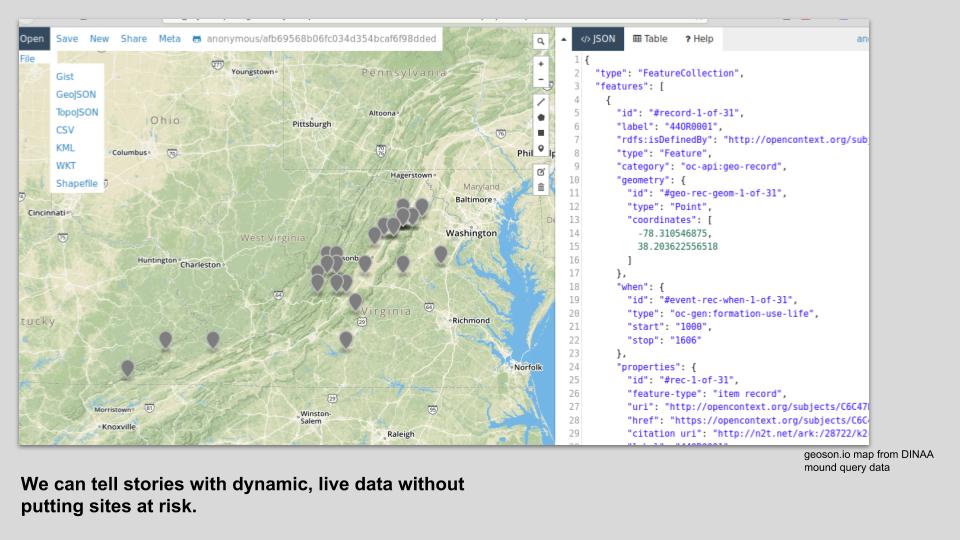

Just a few weeks ago, a researcher inquired about obscured locations to use for a public map showing burial mounds in Virginia. In a matter of minutes, I was able to pull a DINAA query and create a quick interactive GeoJSON map to answer this research question.

See the mound query results for yourself.

In collaboration with the DINAA team, I developed a proof of concept interactive map for disaster response using the same data. This mobile map, or a tool like it, could connect emergency responders to SHPO staff quickly and efficiently (Smith et al. 2017).

View the full paper and try the interactive map.

Sadly, our DINAA data is getting stale. It's from 2013. What's stopping us from building our own API at both a protected and a public scale? We could serve live data straight to DINAA and also use it to create views of data to meet agency outreach and planning needs. Why send all users with varying degrees of experience to a rich-but-confusing VCRIS map viewer when we can tailor data views to answer questions? This approach could streamline agency reviews and help everyone make better decisions. By laying the foundations with documented, controlled vocabularies and making our data available through APIs, we could set ourselves up to connect to repositories like tDAR and other institutional and online repositories.

By opening up this way, I argue we could do more to keep sensitive information safe, as static GIS data and file distribution would continue to decrease. We could reduce duplication of our own effort by eliminating silos. And we could facilitate archaeology outreach in ways that have been impossible before.

Our work will never be done. There will always be material to digitize, files to describe and arrange, data to clean. It’s easy to get frustrated at loose ends and messiness, at red tape and slow bureaucratic timelines. But if we check our perfectionism at the door and strive toward goals of openness and interoperability with the resources we've got, we can tap into something much bigger, a little bit at a time.

Footnotes

1 These aren't all records for buildings, but generally about the above-ground world.

References

Council of Virginia Archaeologists. 2009. “Howard MacCord Resolution.” http://cova-inc.org/News/2009/maccordResolution.PDF.

Library of Virginia. 2004. “A Guide to the Department of Conservation and Development, Division of History, Records, 1927-1950 Conservation and Development, Department of, Division of History 24806a-c , 25913 and 41571.” 2004. http://ead.lib.virginia.edu/vivaxtf/view?docId=lva/vi00960.xml;query=.

Miller, Diane. 1994. “National Register Information Is a Hidden Treasure.” CRM 17, no. 2, page 13.

Smith, Jolene. 2016. “Approaches to Openness.” Society for Historical Archaeology, Baltimore, MD. https://jolenesmith.net/approaches-to-openness/html.

Smith, Jolene, David G. Anderson, Eric Kansa, Joshua Wells, and Stephen Yerka. 2017. “Using the Digital Index of North American Archaeology for Rapid Disaster Response and Reporting.” Keeping History Above Water, Annapolis, MD. https://github.com/aejolene/disastermap.