Approaches, Rationales, and Challenges to Maintaining Site Inventory in the National Parks

For over a century, the National Park Service (NPS) has worked to preserve natural and cultural resources in more than four hundred park units for future generations. In addition, the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) requires all federal agencies to maintain inventories of their historic properties. For decades, the NPS has relied upon three inventory systems: The List of Classified Structures, the Cultural Landscapes Inventory (CLI), and the Archeological Sites Management Information System (ASMIS). These systems began decades ago as paper files and continue today as electronic databases accessed via the internet.

The inventories allow NPS to maintain and update critical information including resource type, location, condition, threats, and disturbances. As the relevant technologies continue to develop with what seems like increasing rapidity, even these relatively modern databases are being rapidly rendered obsolete. The NPS Cultural Resources, Science, and Partnerships directorate has begun work to modernize these systems, and to facilitate their further integration with GIS technologies and other NPS programs, and incorporate elements of the now defunct Ethnographic Resources Inventory (ERI). This paper discusses the issues faced as NPS updates these crucial tools for a second century of service.

I’m David Gadsby. I work in the Cultural Resources, Science and Partnerships Office of the National Park Service, where I coordinate our inventory database of archeological resources. We’re currently working to modernize our inventory systems that track information about historic buildings, cultural landscapes, ethnographic resources and archeological sites, and streamline them into a new online system. You’re looking at the ruins of Casa Grande National Monument. The ruins date to 1400s, protected through citizen activism and presidential proclamation, 1892, declared a national monument in 1918. This is an archeological site -- CAGR00014, with a subsite. The site includes historic and Hohokam features (incl. a drainage ditch excavated by Jesse Fewkes during 1906 stabilization).

It is also more than one historic structure LCS 06607(shelter) On the national register – Designed by Olmsted Co. and Thomas Vint, 01044 (Compound A) (Classic Hohokam, Also on NR).

It is also a cultural landscape – including the visitor center, Casa Grande itself and surrounding vegetation plan – part of a master plan from the 1930s.

In addition to buried archaeological deposits and standing structures, there are facilities (like the walkways) and interpretive signage, not to mention natural resources.

From a park resource management perspective, this is a fairly complex situation, with a large number of resources and resource values packed into a relatively small physical space. It is also repeated at different scales and in different configurations across the seven regions and 417 national park units. Creating a resource inventory system that meets NPS’s diverse and complex needs presents a number of challenges.

This photo is of Keys Ranch, Joshua Tree National Park (JOTR) – it has one or more record in each of three systems: ASMIS, LCS CLI

NPS cultural resources inventory programs track four main types of park Resources:

- Structures - have historic, architectural, or engineering significance

- Cultural Landscapes – defined as historically significant properties that show human interaction with the environment and are eligible for listing on NRHP

- Ethnographic Resources - Sites, structures, objects, landscapes, natural features that have traditional significance in the cultural system of a traditionally associated group

- Archeological resources – known sites on NPS lands that have the potential to yield information about the human past through archaeology.

Individual resources can have more than one resource type, and the physical boundaries and management needs can vary considerably.

For instance, a landscape can be made up of multiple components, including resources that are also archeological sites and structures. By the same token, all or part of a standing structure may also be an archeological site, and sites can be organized differently depending on the management needs of the park and the professional judgement of the archeologists doing the documentation work.

So we need a way to keep track of all this.

Currently, these resources are tracked in four legacy systems:

- List of Classified Structures(LCS)

- Cultural Landscapes Inventory(CLI)

- Archeological Sites Management Information System (ASMIS)

- Ethnographic Resources Inventory (ERI)

With the exception of ERI, which is largely defunct, these systems are built on aging web-accessible sql server platforms that are very similar, but are nonetheless separate systems. The information in them is much older, with some ASMIS records dating back to the 19th century, and the LCS dating as a paper system back to 1960, and as a computer system to 1976.

The current iterations of these systems are very similar in a lot of ways, but all break separately. Unifying into a single system is expected to achieve a number of cost savings and other efficiencies. More importantly, it should allow cultural resource managers in parks to achieve a more coherent view of the resources that they manage.

!

Photo: Former Intermountain Jim Bradford dives the Captain Ed’s Wreck, a submerged archeological site in Biscayne National Park.

The requirements for our systems are laid out in several authorities – laws, regulations, and policy – that require NPS to manage its cultural resources. Here’s a partial list just for archaeological resources.

Beginning with the 1916 Organic act that requires NPS to preserve resources in perpetuity for future generations, to the NHPA’s mandate to inventory historic resources and consider the effects of government decisions on them, to the AHPA’s requirement that the government preserve archeological data, we have a number of particular requirements that we need the systems to fulfill. In addition, restrictions on how those data are managed, such as those restricting the public release of certain information in NHPA section 304 and ARPA section 7 place further requirements on any new system. Many of these statutes, like GRPA come with reporting requirements, so we need to be able to extract fairly specific kinds of data.

Photo: Square Tower House at Mesa Verde National Park

Here are the basic things we need to be able to do:

Additionally, the structure of the NPS, and wide variation in the types of resources and level of staffing available to manage them mean that the requirements across the system vary a good deal. Managing what users are able to see and ensuring that appropriate staff have access to the records they need is really important, and throws a lot of complexity into the system.

The need for certain key fields, (like location fields) to remain secret is in tension with the need to share information across disciplines, and especially with planners, facilities people, and first responders in the event of a disaster. We’ll talk about that problem in detail in another session Saturday afternoon.

BELA Good Hope Reindeer Herding Site

Clear mandates in the form of laws, regulations, and policy, as well as a recent commitment of funds from the

Institutional experience Large user base means lots of expertise (comes with risk of losing that information)

St Louis Arch at Gateway Arch NHP

Aside from the usual dearth of staff, money, and time, some of the challenges specific to management of NPS operating environment are:

Costs and Inefficiencies of maintaining separate legacy data systems: - Legacy data is important, particularly as we witness increasing levels of change on the ground. - The systems, and particularly the web applications that provide access are less important, and can hamper access and usability. - We have three, and when they break, we have thrice the maintenance costs. When we update we do it three times. - Old applications are more vulnerable to security threats.

Maintaining systems at the speed of government - Old designs mean lots of maintenance, particularly as web standards, web browsers, and computers themselves modernize. - For example, woke up one morning to discover that several features of ASMIS depended on were no longer supported by Chrome, and users could no longer enter data using that browser. - Older, static designs are harder to update and enhance. Some mistakes get fossilized in the system. E.g. string fields that shouldn’t be, lack of GIS-friendly location data, pick lists that used to be free text. - Technology in industry moves much faster than government budget cycles. NPS plans some of its spending 1 year out, and some up to 3 years out. - This means that in the time you’ve taken to fund an intended purchase, the item/software/technology you’ve planned to acquire can become obsolete. - We don’t have the budget and spending capacity or flexibility to drive or keep up with industry.

Maintaining a data system that works for all users: NPS has 417 park units across the United States and in the territories. This means wide variations in staffing, logistics and infrastructure, data needs, internet connectivity.

Some parks have large archeological staffs, but many have none. Some regions have large service centers, while others have smaller programs. Different models = different needs, different terminology, different theoretical approaches. (and theory effects how you collect and store data.)

Combine that with the fact that we’re now planning to merge inventory systems into a new system. So now you’re adding architects, landscape architects, and ethnographers, all with different levels of training, needs, priorities.

In order to have meaningful data, you have to have a fairly high level of complexity, both in terms of user access and the structure of the data system. (You can have simple, and you can meet meet the specific needs of a variety of users, but each comes at the cost of the other. )

Also have to balance the expectations of users with what is achievable, and sensible. Too many moving parts means more to break, higher maintenance costs.

Security Two worries – inappropriate access by people using the system as intended, and hacking breach. Both need to be avoided, both present challenges. First – inappropriate access by users, means thinking through and carefully testing, particularly when security change can ramify throughout the system. Second is up to people at a higher pay grade to designate cybersecurity standards and provide appropriate infrastructure. But we’ve had to adapt legacy systems to ever more stringent requirements from Information resources people ( DOI OCIO, for instance). Doing so invariably breaks those systems.

The hazard with both types of security is that appropriate users must have good access.

Mission Nuestra Señora de los Ángeles de Porciúncula de los Pecos (Pecos Church/Mission/Covento) In all three databases

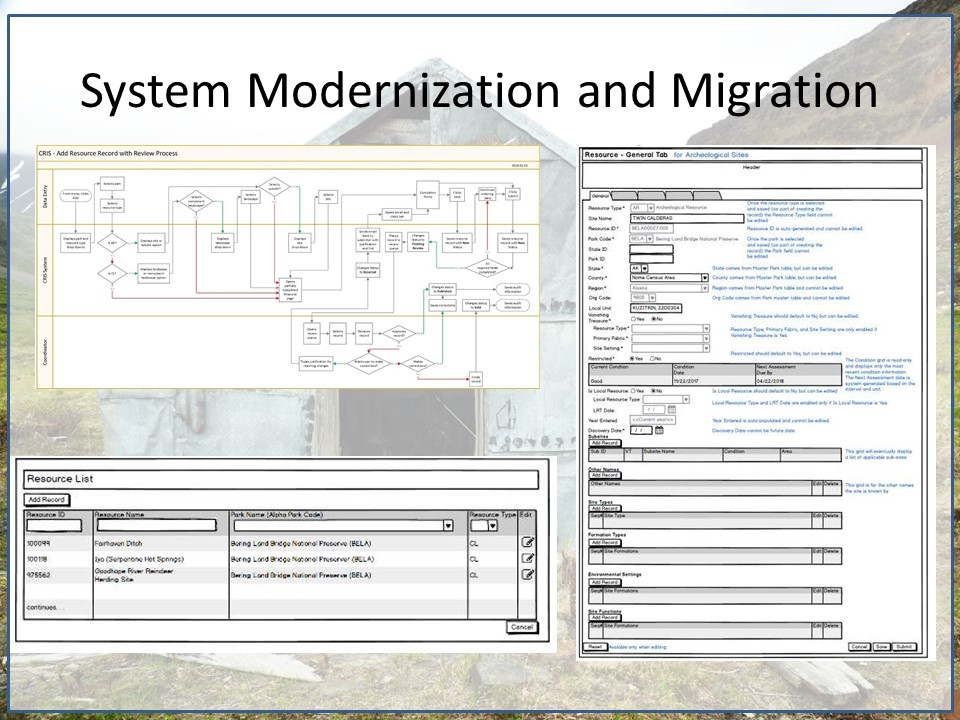

Images are samples of workflows and data entry features for the new system. Used with permission.

My current project is to integrate the four legacy databases into one, and develop a web-accessed application. Working name is CRIS or CRIS-P We are currently in the throes of first year, half million dollar contract. I’d hoped to have something to demo, but it isn’t available yet.

Tasks: - Contractor designs new database, GUI, reports and utilities. - Migrating data from legacy databases to new - Updating problem fields and pick lists

For the future: - Additional reports - Crosswalk to other databases - GIS integration

CAGR again

When we’re done with this first year, we’ll have a stable system that works in the field, but that will still need improvement. We’ll continue to improve into the out years so that we’re meeting user needs as best we can.

2016 Archaeoblitz @ KNRI

Aside from the most basic needs – fulfilling statutory requirements, creating accurate records, saving money on system maintenance, we expect some other benefits to arise from the unified approach to inventory data. - Particularly park managers will be able to able to see /report on at least some information about all of their park’s cultural resources in a single system. - Data collection in the field on any devise - Record and preserve institutional knowledge - Long-term projects with ever-deeper time depth. E.g. Cochran et al ( in prep) on climate change (http://www.georgewright.org/1706cochran.pdf)